#Pratchat61 Notes and Errata

These are the episode notes and errata for Pratchat episode 61, “What Terry Wrote“, discussing the 24th Discworld novel, 2005‘s Thud! with guest Matt Roden.

Notes and Errata

- The episode title plays with “What Tak wrote”, the creation myth of the dwarfs, as featured at the start of Thud!

- For those interested, here’s the Pratchat intro script as it appears in our episode notes template. Ben updates it when creating the notes for a new episode, inserting the book’s title and the details for the guest.

LIZ: I’m Elizabeth Flux. BEN: I’m Ben McKenzie. LIZ: Welcome to Pratchat, the monthly Terry Pratchett book club podcast. BEN: Each month we discuss one of Terry Pratchett’s books with a special guest. LIZ: This month we’re reading Book Title, [pun/joke about the book]. BEN: And our [returning] guest is [descriptors], [guest name] - welcome [guest]!

- 100 Story Building and Story Factory are not-for-profit creative writing centres for children and young people which run workshops centred around storytelling, literacy and writing, mostly in schools. Both were inspired in large part by 826 Valencia, a creative writing centre for established in San Francisco in 2002 by educator Ninive Caligari and novelist Dave Eggers (of McSweeney’s fame). Other similar organisations exist in many countries, including The Ministry of Stories in London (with which Matt was involved) and Fighting Words in Dublin.

- A geode is a hollow, rounded sedimentary or igneous rock (and we’ll come back to that term) which has minerals on the inside of the hard outer shell. Those minerals often include crystals, like quartz or amethyst. Igneous geodes are often formed when there is a bubble of gas inside a flow of magma or lava. They’re very popular as jewellery and ornaments, and are often cut in half for display, with the flat edge of the shell polished to show off its formations too. They’re not to be confused with thunder eggs, which are similar but distinct spherical structures also formed in lava.

- Octarine – the eighth colour, the colour of magic – is last definitely mentioned before Thud! in The Last Continent, back in 1998. (It might also be mentioned in The Last Hero, though this is harder to verify without re-reading the whole book.) It does get a passing mention in The Science of Discworld III: Darwin’s Watch, but only in a non-fiction chapter.

- Detritus and Cuddy, the Watch’s first troll and dwarf recruits, argue – and become fast friends – in Men at Arms. We discussed the book all the way back in #Pratchat1, “Boots Theory“, and revisited in the live special #PratchatNALC, “Twice as Alive“.

- The “dwarf and the troll in the rock band together” are hornblower Glod Glodsson and percussionist Lias Bluestone who form a band with Imp y Celyn’s in Soul Music. We discussed the novel in #Pratchat19, “It Don’t Mean a Thing If It Ain’t Got Rocks In“.

- Rush Hour is a 1998 action comedy directed by Brett Ratner and starring Jackie Chan and Chris Tucker as Detective Inspector Lee from Hong Kong and Detective James Carter of the LAPD. Lee is summoned to Los Angeles to help rescue the kidnapped daughter of his former boss, and Carter is assigned to “babysit” him as punishment, making him determined to solve the case. It was a big hit, spawning two sequels: Rush Hour 2 in 2001, which moved the action to Hong Kong, and Rush Hour 3 in 2007, which took both officers away from home to Paris. There have been rumours of a fourth film for years, and in this era of legacy sequels who knows – it could still happen.

- The Wire is an American crime television series created for HBO by David Simon, an American author and former crime reporter. It’s set in the city of Baltimore, in the US state of Maryland, and each season explores a different group connected to crime and law enforcement, though drug gangs and the police appear in all five seasons, which were first broadcast between 2002 and 2008. Season four, the one specifically mentioned by Matt, deals with the education system and the mayor’s office. The Wire notably stars Wendell Pierce as William “The Bunk” Moreland, a homicide detective who features in all five seasons; you might know him as the voice of Death in BBC America’s The Watch. (See #Pratchat52, “A Near-Watch Experience“.)

- We’ll mention the earlier Watch novel, The Fifth Elephant, quite a few times this episode. It introduced the idea of the Deep Downers and is the origin of a lot of Discworld dwarf culture, previous books having mostly stuck to a parody of Tolkien’s dwarfs. It also announced the impending arrival of Young Sam We discussed it in #Pratchat40, “The King and the Hole of the King“, back in February 2021.

- Fizz, the political cartoonist for The Ankh-Morpork Times, is named for Phiz, the pen name of popular Huguenot illustrator Hablot Knight Browne (1815-1882). His inclusion here (and in Monstrous Regiment) reflects that he contributed cartoons for the British satricial magazine Punch in very much the same style, but Browne was also known for illustrating novels and serialised stories in more reputable publications, most notably for Charles Dickens’ Pickwick Papers, which started with the pseudonym Nemo before changing it to Phiz. “Phiz”, by the way, is short for “Phizzog”, an English slang term for face which is derived from the word “physiognomy”, which means “a person’s facial features or expression”. (We’re not sure which came first, the cartoonist’s tag or the slang term, but its a fun word all the same.)

- The Good Wife is a CBS legal drama set in Chicago, which ran for seven seasons between 2009 and 2016. It stars Julianna Margulies as Alicia Florrick, a woman who restarts her legal career as a junior lawyer when her State’s Attorney husband is jailed for corruption. It was followed in 2017 by The Good Fight, a spin-off starring Christine Baranski as her The Good Wife character Diane Lockhart, a senior lawyer at Florrick’s firm who has to start over at a new one after her daughter is scammed, resulting in financial disaster. It ran for six seasons between 2017 and 2022. We previously mentioned both shows in #Pratchat51, “Boffoing the Winter Slayer“. The Good Dwarf could deal with similar themes of what women are expected to give up for men, but adding in the unique species and gender angles of Discworld dwarfs. Don’t forget to tell us which characters you think should be in it!

- Code-switching is originally a linguistic term for when a multi-lingual speaker changes between languages (or varieties of the same language) in the same conversation. This usage dates back to 1951 with the book Language of the Sierra Miwok by Lucy Shepard Freeland, when she notes it in the context of Californian First Nations people. Code-switching involves a great deal of mental energy as different languages have very different structures, idioms and modes of speech, and multilingual speakers often have to switch for their own needs as well those of the people they’re speaking to. The term has seen expanded use to mean switching between any two different modes of speaking (or thinking), especially when it comes to different levels of privilege, expected gender roles, and neurodiversity.

- The Da Vinci Code was Dan Brown’s smash hit novel from 2003 (two years before Thud!), the second to star Robert Langdon, a university professor who specialises in religious iconography and “symbology”. Langdon, who was introduced in Brown’s 2000 novel Angels & Demons, would appear in four more books. The Da Vinci Code‘s plot uses ideas from earlier writings about the Holy Grail and the Templars, and kicks off when professor is murdered to protect a secret about Christ which was uncovered by Leonardo da Vinci, who left clues in his paintings – most notably The Last Supper. It was controversial for its portrayal of the Catholic Church (who employ assassins in the book) and Christianity in general, as well as for its cavalier attitude to religion, history and art – Brown claimed in interviews that the background history he used for the book was “all” or “99%” true, including the existence of secret societies generally considered fictitious. In 2005, the same year as Thud!, Tony Robinson – comic actor, Discworld audiobook narrator and presenter of Time Team – produced The Real Da Vinci Code for Channel 4, in which he debunked many of the supposed historical facts mentioned in the book. This didn’t hamper the book’s immense popularity, though, and in 2006 it was adapted for film by Ron Howard, with a script by Akiva Goldman and starring Tom Hanks as Langdon. The film was followed by adaptations of Angels & Demons and the fourth Langdon novel, Inferno.

- A cyclorama (not “cyclodrama” as Matt says, though we’re all for drama in the round) is the Roundworld equivalent of Ransom’s painting in the book: a panoramic painting intended to be displayed on the inside of a cylindrical platform, surrounding the viewer. The term is also used for the building or room designed to hold such a painting. They were apparently very popular in the late 19th century. These days “cyclorama” is more commonly used to refer to the all-white backdrops used on stages, or in photography studios, where they are curved to give the illusion of there being no background at all.

- Mr Sheen is an Australian brand of cleaning products – specifically an aerosol-based surface polish – created in the 1950s. They were popular well into the 1990s, remembered for their mascot, a small Mr Magoo-like cartoon figure with a large shiny forehead and glasses, and his catchy advertising jingle. He found success in other markets, too, notably the UK, where the Australian mascot was replaced by a moustached flying ace who flew around the house on a can of the product. “Mr Shine” has also been used as a name by many cleaning companies and products, though none of them seem famous enough to be a direct reference.

- The city of Dis appears in Inferno, the first part of Dante’s The Divine Comedy, where it encompasses Lower or Nether Hell – which are the sixth, seventh, eighth and ninth circles, housing those souls whose sins were willing or “obdurate” (i.e. unrepentant) – in order, those of heresy, violence, fraud and treachery. The city’s outer walls are surrounded by the River Styx, which forms a moat. Its name is derived from Virgil’s Aeneid, which refers to the Underworld as “the realms of Dis”, and mentions its “mighty walls”. “Dis Pater”, Latin for “Father of Dis”, was also the ruler of the Underworld in Roman mythology.

- The Gooseberry is most obviously a pun on the Blackberry, the early smartphone which was a little ahead of its time, but nonetheless popular with high-powered business folks in the 1990s and 2000s, before the advent of touch-screen smartphones with the iPhone and its competitors. It might also be a reference to UK slang, in which a “gooseberry” is like a “third wheel” – someone who feels a bit unnecessary or left out in company, usually a couple.

- “Unrelenting standards” is a psychological term for internal pressure to perform well, manifesting as perfectionism, difficulty in gauging one’s own performance compared to what’s generally considered acceptable, a desire to avoid criticism or mistakes, and an obsession with productivity and efficiency. It’s often said to be a product of growing up being valued primarily for your achievements, or in an atmosphere of frequent criticism and little praise.

- We’ve previously mentioned the Love Languages in #Pratchat46, “The Helen Green Preservation Society“. They originate in the 1992 book The Five Love Languages: How to Express Heartfelt Commitment to Your Mate, which was written by Gary Chapman, a Baptist pastor and radio host. The book was phenomenally successful, selling more than 11 million copies and spawning many sequels and imitators. Ben is not a fan because the idea is very reductive; psychologists and counsellors have criticised Chapman’s work for over-simplifying and homogenising human experiences of love and communication, even where they appreciate the metaphor and have tried to expand it. Other critics note that Chapman is not professionally trained in psychology or counselling, holds some deeply conservative and homophobic views, and based his book on his experience with a fairly narrow sample of his parishioners. He also rejects any expansion of the idea. perhaps because its made him a great deal of money… For the record, his original five love languages are “Acts of Service”, “Words of Affirmation”, “Quality Time”, “Receiving Gifts” and “Physical Touch” – which you can probably see already leaves out a lot.

- For more about Moving Pictures as a horror story, see our discussion in #Pratchat10, “We’re Gonna Need a Bigger Broomstick“.

- Stephen King’s “Tak” appears in his 1996 novels Desperation and The Regulators, the latter of which was published under King’s outed pen name Richard Bachman, claiming to be a novel Bachman had written years earlier. Instead, it’s intentionally a story set in a parallel universe to Desperation, with alternate versions of many of the same characters – including the author!. Like the Summoning Dark, King’s Tak comes out of a deep mine in the desert and inhabits a human host – in Desperation it is a police officer who becomes a sort of berserker. We won’t say too much more, but as Ben mentions in the episode, the similarities don’t go much further than that, but it might be a deliberate reference.

- The HBO miniseries starring Ben Mendelsohn is the 2020 adaptation of another Stephen King book, 2018’s The Outsider, which does indeed have a similar plot.

- “And then the car ate a person I guess?” is a reference to Stephen King’s Christine, a 1983 novel about a seemingly possessed, jealous and violent classic car named “Christine”. It was adapted the same year into a film by John Carpenter, with some details – notably the source of the car’s demonic presence – changed considerably. Carpenter directed it as a career-saving move after his previous labour-of-love film, The Thing, didn’t do well at the box office, but both films are now cult classics. A remake of Christine is rumoured to be in production.

- A “cryptex” is a small container with a secure, complex lock, intended to carry secret messages. The term – a portmanteau of “cryptic” and “codex” – was invented by Dan Brown for The Da Vinci Code, though there’s nothing about the device itself that requires the use of cryptology to use. The original version in the novel is a hollow cylinder made of stone and brass with five rotating sections, each containing every letter of the alphabet (though whether it’s the Latin or modern English alphabet is unclear). This makes it basically a letter-based combination lock with between 280,000 and 11 million possible combinations, depending on some details not given in the novel. Physical reproductions of the cryptex have become widely available since the release of the Da Vinci Code film; Ben has even used one as part of an escape room experience he designed.

- We mention that on the Discworld, werewolves are classified as undead, something which dates back to Angua’s first appearance in Men at Arms. We’ve never really agreed; see above for our episodes about the book, where we decide they are, if anything, “twice as alive”.

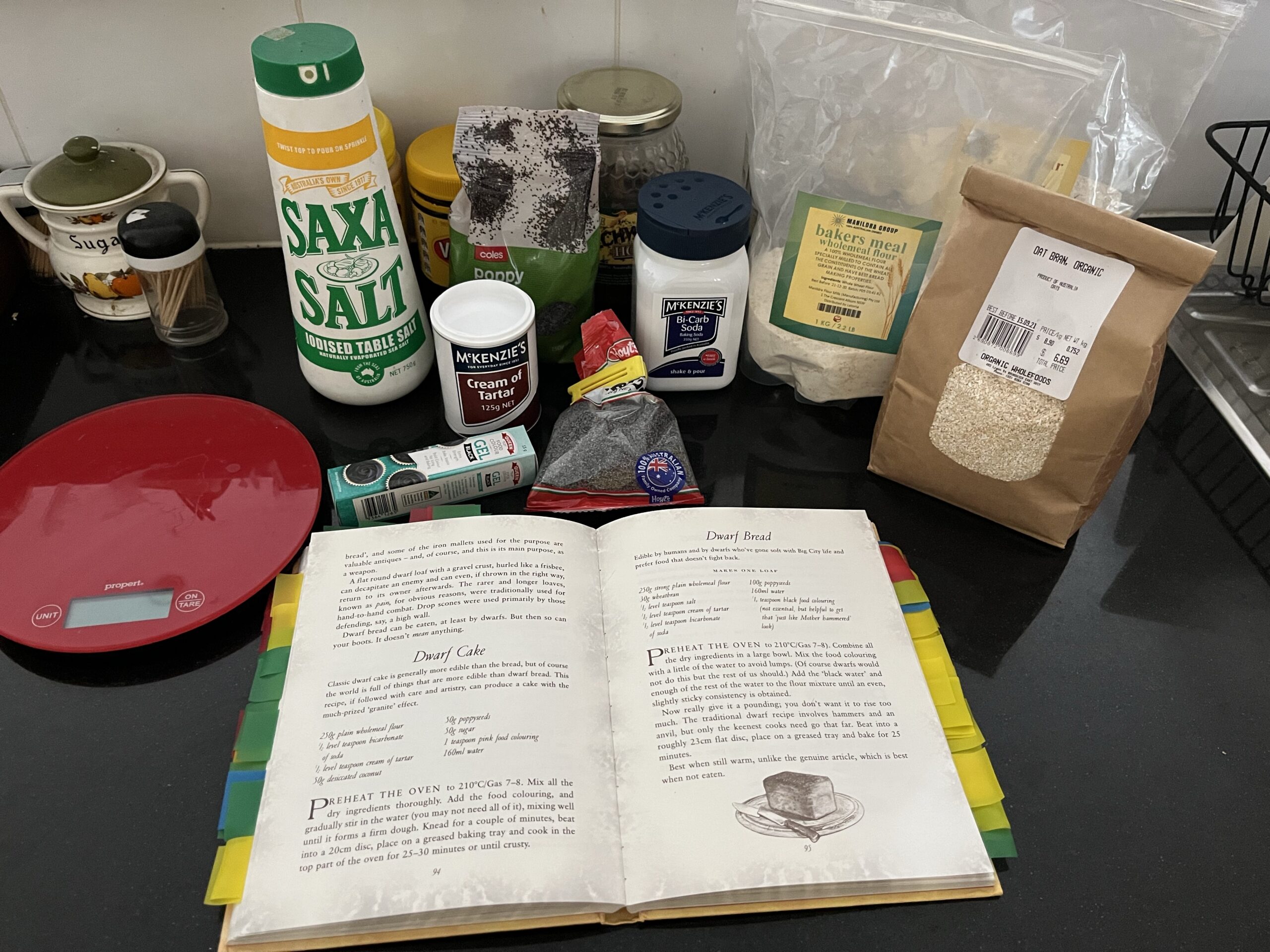

- “A Collegiate Casting-Out of Devilish Devices” is the fifth and final Discworld short story, first published in the Times Higher Education Supplement in May 2005, just four months before Thud! We’ll be discussing it in #Pratchat63, coming in January 2023.

- “Fracas“, along with “rumpus”, are both used by William de Worde during a meeting with Lord Vetinari in The Truth. A footnote describes them as the word equivalent of rare fish, claiming that they are “found only in certain kinds of newspapers” and “never used in normal conversation.” For more on this, see #Pratchat42, “Truth, the Printing Press and Every -ing“.

- Liz mentions “Incepting The Wire“; she’s invoking the concept of “inception” from Christopher Nolan’s 2010 film Inception. The film is about a crew of criminals who use technology to enter the dreams of others, stealing important secrets from their subconscious. The plot of the film involves the crew being hired for the more difficult crime of “inception”: inserting an idea into the mind of the target.

- We Own This City is a 2022 television mini-seres created by David Simon for HBO. Like The Wire, it’s set in Baltimore and is about law enforcement – in this case, corrupt members of the Gun Trace Task Force, based on real-life events which occurred between 2015 and 2019.

- The Descent is a 2005 British horror film written and directed by Neil Marshall. Ben doesn’t necessarily recommend it, especially if, like him, you’re not really a horror fan – it’s pretty full on. Ben prefers the director’s previous film, the 2002 black werewolf comedy Dog Soldiers, but The Descent was pretty successful. A sequel, The Descent Part 2, was released in 2009, though it was directed by Jon Harris, who edited the original. It’s considered to be…not as good.

- When Detritus is in the desert of Klatch in Jingo, he initially has a lot of trouble in the heat, especially as his helmet conks out. Later, at night when the desert is very cold, his brain cools and becomes more efficient, as he puts it. Sadly he doesn’t say anything about the apparent demise of his helmet; the relevant passage is quoted below, and the helmet isn’t mentioned again. See also our discussion of the novel in #Pratchat27, “Leshp Miserablés“, and our next episode, #Pratchat62, “There’s a Cow in There“, when we mention the helmet again.

The troll was standing with his knuckles on the ground. The motor of his cooling helmet sounded harsh for a moment in the dry air, and then stopped as the sand got into the mechanism.

Jingo – Terry Pratchett, 1997

- Matt mentions Brick’s stream-of-consciousness passages read like “an excerpt from an Irvine Welsh novel“. Welsh is a Scottish author, most famously of Trainspotting, the 1993 novel about a group of addicts – of heroin or other things – that was adapted into film by Danny Boyle in 1996. Both book and film are considered classics.

- Matt’s “dribbling dragon” is an allusion to “Chekhov’s gun” (originally “Чеховское ружьё”, or “Chekhov’s rifle” in Russian), advice given by the Russian playwright Anton Chekhov in several letters to younger writers in the early twentieth century. It’s basically the idea that you should only include necessary details in your story – the usual example being that if you include a gun in the first act of your story, it should be used to shoot someone before the end of the play or else taken out of the story entirely.

- Reg Shoe, revolutionary-turned-zombie-turned-activist-turned-police detective, is not at all mentioned in Thud!, despite having a prominent supporting role in the two preceding Watch novels, The Fifth Elephant and Night Watch. Angua does mention in passing to Sally that “no-one cares if you’re a troll or a gnome or a zombie or a vampire”, but that’s as close as it comes. Vimes doesn’t even think of Reg during the flashback to his meeting with the Patrician about Sally, when he mentally lists the weirder members of the Watch: he thinks only of trolls, dwarfs, golems, a werewolf, an Igor and Nobby.

- We’ve mentioned the British drama Downton Abbey a few times before on the podcast, most notably in #Pratchat36. The series was created and co-written by English actor, writer, director and actual aristocrat and member of the House of Lords, Julian Fellowes. It follows the inhabitants of the titular manor house: the aristocratic Crawley family, led by Lord Grantham, and their servants. It’s set between 1912 and 1925 and features many significant historical events, including the sinking of the Titanic, the Great War, and the Spanish Flu epidemic. (Of note: Mary Crawley, eldest daughter of Lord Grantham, is played by Susan Dockery, known to Discworld fans as Susan in the television adaptation of Hogfather.) It ran for six series on ITV between 2010 and 2015, and became a worldwide phenomenon, especially after it was added to the streaming service Netflix. The story has since been continued in two films: Downton Abbey in 2019, set during a visit by the royal family to Downton in 1927, and Downton Abbey: A New Era in 2022, set in 1928 and involving a film crew hiring the Abbey as a location, and the family going on a trip to France to visit a villa the Dowager Countess (played by Maggie Smith) is bequeathing to one of her great granddaughters. Fellowes also created the HBO series The Gilded Age, set in 1880s America, and there’s been talk of potentially featuring a younger version of Smith’s character in that show.

- When Ben mentions “the witch in that Tiffany Aching book“, he’s referring to Miss Level, the witch with two bodies – kind of the opposite of Miss Pickles and Miss Pointer – who mentors Tiffany in A Hat Full of Sky. For more on that, listen to #Pratchat43, “Big Wee Hag: Far Fra’ Home“.

- The Leonardo DiCaprio pointing meme is an image of the actor character Rick Dalton pointing at a movie screen when he sees himself, taken from the film Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019, dir. Quentin Tarantino). It’s often used in conjunction with a quote, retweet or another image to show the poster self-identifies with it. We previously mentioned it in #Pratchat36, “Home Alone, But Vampires“, and #Pratchat43, “Big Wee Hag: Far Fra’ Home“.

- Ben hasn’t yet confirmed whether its Mr Shine or Grag Bashfulsson who warns Vimes he might have to rein in his anger more than usual, but he’ll keep looking.

- Vetinari worries he’s pushed Vimes too far in Men at Arms, though Ben has the reasoning backwards – he’s worried because, as he mentions to Leonard da Quirm, Vimes didn’t punch the wall.

- Tracey Emin is a British artist known for her personal, confessional works in a variety of media, and was considered an enfant terrible of the Young British Artists (or YBAs) in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Her most famous piece is probably Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995, a tent appliquéd with the names of all her sexual partners, which was destroyed in a fire in a storage facility in 2004. The “modern” artworks mentioned in the book are by Daniella Pouter, and include Don’t Talk to Me About Mondays, described as a pile of rags, which might be a reference to Emin’s famous 1998 work My Bed, literally the artist’s bed piled with items from her bedroom in disarray.

- “The Peaky Blinders thing” is a reference to the flat caps with sharpened pennies sewn into the brim, used as concealed weapons by Willikins street gang. The real “Peaky Blinders” were a street gang in Birmingham in the 1880s through to the 1910s; there’s a story that they used caps with razor blades sewn into them as weapons, leading to the gang’s name, but the name pre-dates disposable razor blades so this is probably apocryphal. A more sound theory is it referred to their sartorial style: they did wear flat caps, but also dressed rather well for a street gang, so the name probably referred to the hats and that they were fancy, as “blinder” is Birmingham slang for “dapper”. Another possibility is their technique of grabbing a robbery victim’s hat from behind and pulling it down over their eyes, so they wouldn’t be seen and couldn’t be identified. The term has become popular again since the BBC series Peaky Blinders gained popularity, though it’s a heavily fictionalised version of the real gang. It ran for six series between 2013 and 2022.

- We heard the story of Michael Williams’ 2014 interview with Pratchett during the recording of #Pratchat26, “The Long Dark Mr Teatime of the Soul“, and we included his story in the third episode of our subscriber bonus podcast, Ook Club. You can hear the full discussion as “Imagination, Not Intelligence, Made Us Human” on the Wheeler Centre website…or you could. Now, instead, we direct you to the video of the discussion on YouTube. There’s a lot of good stuff in it!

- If you’re interested in a full count of who dies in the Discworld books, you’re in luck: The L-Space Web fan site has just such a record! Like a lot of things on L-Space, “The Death Lists” wasn’t maintained all the way to the end of the series, but peters out around the time newsgroups and static websites were being replaced by social media and wikis. But, in this case, it only goes up to Thud! so happily (if that’s the right word) it covers most of the books we’ve discussed on the podcast up to this point. Though you might want to take it with a grain of salt – we note the Thud! entry doesn’t seem to include the four mining dwarfs left to die under Ankh-Morpork after hearing what the Cube had to say…

- Ben would like to apologise for being needlessly pedantic about the two Discworld books which don’t feature Death, and his roasting at Matt’s hands is well deserved. Despite that, we can confirm he remembered correctly that they are The Wee Free Men (which we covered in #Pratchat32, “Meet the Feegles”) and Snuff. The Reaper Man thing is absolutely not true, do not go back and check or listen to #Pratchat11, “At Bill’s Door”.

- The Thing appears in the Bromeliad, mostly the first and final books Truckers (see #Pratchat9, “Upscalator to Heaven”) and Wings (see #Pratchat20, “The Thing Beneath My Wings”). In those books the Thing is a small, seemingly indestructible black cube passed down through generations of Nomes to Old Torrit and then Masklin, which used to occasionally speak and provide advice. When Masklin brings it to Arnold Bros, it recharges itself using the Store’s electricity and reveals that it is “Flight Recorder and Navigation Computer of the Starship Swan”, helping Masklin with a lot of his plans to get the Nomes out of the Store and eventually back to their home planet. Cube-shaped computers and recording devices also appear in other media, most notably in Star Wars, where both the Jedi and the Sith store holographic recordings on “holocrons” which are commonly cube-shaped.

- The main mentions of school projects in Pratchett’s work occur in the Johnny books. In Chapter 5 of Johnny and the Dead, Johnny uses the excuse of a school project to ask about the surviving member of the Blackbury Pals, claiming that “You could get away with anything if you said you were doing a project.” He uses this trick again in Johnny and the Dead in order to speak to Mrs Tachyon when she’s in hospital, and his legit history project comes in handy when the kids have to disguise themselves for a trip back in time to the 1940s.

- Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971) is a Disney musical blending live-action and animation, much like Mary Poppins. Also like Mary Poppins, its based on novels for children by an English author, in this case Mary Norton’s The Magic Bedknob; or, How to Become a Witch in Ten Easy Lessons (1944) and Bonfires and Broomsticks (1947). The protagonist, Ms Eglantine Price (played by Angela Lansbury in the film, in her screen musical debut), is a single woman living in a coastal village in Dorset during World War II who is, against her will, saddled with some children evacuated from London. They discover Ms Price is learning witchcraft by correspondence, and end up joining her on an adventure to complete her education and locate a powerful spell she believes can aid in the war effort. It’s not specifically included in the list of Pratchett Family Movies (or PFMs) mentioned in a footnote in Chapter 9 of A Life With Footnotes, but it wouldn’t look out of place next to the likes of Time Bandits, The Princess Bride and Ladyhawke.

- Irish, British and American actor Angela Lansbury (1925-2022) had a long and distinguished career on stage and screen. She is best remembered as Jessica Fletcher, the crime writer protagonist of the popular American cosy mystery TV series Murder, She Wrote, which ran for twelve seasons between 1984 and 1996, followed by four TV movies up until 2003. But she was also an accomplished singer, and played many famous roles in stage musicals including being the original Mrs Lovett in Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, and Mrs Potts in the Disney film Beauty and the Beast. Her last role being a cameo appearance as herself in Ryan Johnson’s Glass Onion in 2022, and she died on 11 October, 2022, not long before we recorded this episode.

- In Thud!, while complaining to Cheery about the announcement in the Times that the post office is issuing memorial Koom Valley stamps, Vimes says “Remember the cabbage-scented stamp last month?” This is an unusually direct reference to the events of the immediately previous Discworld novel, Going Postal (see #Pratchat38, “Moisten to Steal”). In Chapter 12, once stamp collecting has started to take off, Junior Postman Stanley Howler presents his own design to Moist for a stamp depicting a cabbage, printed with cabbage ink and using gum made from broccoli: “A Salute to the Cabbage Industry of the Sto Plains”. This directly links the two books as being closer in time than the gap between their publication, and reinforces the basic idea that the Discworld books more or less happen in the order in which they’re published, with a couple of notable exceptions.

- Ridcully certainly has a busy month. The above link suggests that there is less than a month between Ridcully overseeing Moist’s race against the Clacks in Going Postal and tricking out Vimes’ coaches in Thud! Ridcully also appears at an important meeting near the end of Making Money, and also has his head printed on the fee-dollar note when Moist introduces paper money in the final chapter. Of note: The Science of Discworld III (see #Pratchat59) and the short story “A Collegiate Casting-Out of Devilish Devices” (see #Pratchat63) were also published the same year as Thud!, so Ridcully may also be dealing with A. E. Pessimal’s inspection and an invasion of Auditors into Roundworld at around the same time. A busy month indeed!

- Brian Blessed (b. 1936) is an English actor from Yorkshire who is known for his booming voice. His best-known roles include King Richard IV in the first series of Blackadder, Prince Vultan of the Hawkmen in the 1981 film version of Flash Gordon, and the voice of Boss Nass in Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace. But he’s been a fixture of British television, stage and film for years, popping up in memorable guest roles in Space: 1999, Blake’s 7, Doctor Who and many more. As well as many cult films of the 1980s, he’s been in Kenneth Branagh’s Shakespeare films Henry V (1989), Much Ado About Nothing (1993) and Hamlet (1996). Of note to Terry Pratchett fans, he appears as William “Bill” Stickers, deceased communist, in ITV’s 1995 adaptation of Johnny and the Dead.

- Lord Melchett, played by Stephen Fry, is another character from the British sitcom Blackadder. He appears in the second series, Blackadder II, as an obsequious member of the royal court and Lord Edmund Blackadder’s rival for the favour of Queen Elizabeth I. In this instance, though, Ben is really thinking more of Lord Melchett’s descendent, the Blackadder Goes Forth character General Melchett (also played by Fry), who is more over-the-top eccentric and dangerously in charge of British soldiers on the front line during World War I.

- We’ve mentioned Back to the Future before, most recently in #Pratchat54, “The Land Before Vimes”, our discussion of Night Watch. In the film, eccentric scientist Doc Brown creates a time machine using a DeLorean sports car. Its time travel device, the “flux capacitor”, requires the vehicle to travel at 88 miles per hour (about 142 kilometres per hour); when it hits that speed the car and its occupants are instantly transported to the destination point in time, leaving behind flaming tyre tracks. At the end of the first film, Doc returns from a trip to the future to take his young friend Marty “back to the future”; Marty worries they don’t have enough road to get up to 88mph, to which Doc famously replies “Roads? Where we’re going, we don’t need roads.” The DeLorean then begins to fly… Pratchett was a fan of the film – the biography A Life With Footnotes recounts the story of the time he almost bought a replica of the DeLorean time machine – and he previously referenced it in Soul Music, in which Binky leaves flaming hoof prints behind when he travels time-bendingly fast.

- George R. R. Martin is the bestselling author of the A Song of Ice and Fire fantasy series of books that begins with A Game of Thrones. The series was famously adapted for television by HBO as Game of Thrones. The novels are very long, but don’t all cover the same amount of time; by some estimates, the narrative time that passes varies between as little as a few months to more than a year. And then you have to factor in that the seasons of the world of the book are also irregular, for undisclosed fantastical reasons…

- Listener Graeme Kay sent us in his tip that he thinks Koom Valley might be based on a place in Far North Queensland, not least because Pratchett is known to have spent plenty of time on holiday in that part of Australia. The specific place Graeme was thinking of is at Babinda Boulders on the land of the Yidindji people south of Cairns. Graeme mentioned “The Devil’s Pool”, but it’s one of several specific spots at Babinda which are connected by rushing water (the others are “The Chute” and “The Washing Machine”). Despite warning signs and local oral traditions about Siren-like dangers, younger tourists continue to visit those parts of the Boulders. More than twenty people have died there in the last century or so, largely because of underwater hazards that make it very difficult to survive being dragged under by the current. Those hazards do sound very similar to the ones encountered by Vimes in Koom Valley, and which would have surely killed him if not for the influence of the Summoning Dark. Sadly this is not a phenomenon of the past; the latest death occurred in December 2021, and a recent safety review completed in January 2023 recommended better signage to try and prevent more deaths. You can read about that, and see pictures of the location and diagrams of the hazards there, in this ABC news article.

- We discussed Carpe Jugulum, the last of the witches books, in #Pratchat36, “Home Alone, But Vampires”.

- Granny Weatherwax battles with her sister Lily in Witches Abroad. It’s never stated clearly, but it’s suggested that Lily is older than Granny, though her use of magic makes her look younger. She’s never described as her twin.

- Granny doesn’t say anything about it, but in Carpe Jugulum when she is fighting the influence of Count de Magpyr, she has to choose between the darkness and the light to escape the lands of Death. In the end, she faces the light…and steps backwards. A very Granny Weatherwax solution, and reminiscent of her dilemma in the mirror dimension in Witches Abroad.

- Liz says “Revved up like a deuce”, which is a lyric from “Blinded by the Light”, a song by Bruce Springsteen released on first album, 1973’s Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. It was famously covered by Manfred Mann’s Earth Band on the 1976 album The Roaring Silence, and that version was a top ten hit in several countries.

- We’ve previously mentioned Sophie’s Choice, the 1979 final novel by American author William Styron, which was adapted into a film in 1981 starring Meryl Streep, Kevin Kline and Peter MacNicol. While it’s meant to be a surprise revelation in the story, it’s now famous for Sophie – a Polish immigrant who escaped Nazi Germany – having to choose which of her two children would be killed when she was sent to Auschwitz, with both of them being killed if she refused to choose. It’s since entered popular culture as a shorthand for an impossible (or at least very difficult) choice.

- We mention a few famous fictional butlers this episode, including Alfred Pennyworth (Batman), Mr Butler (Miss FIsher’s Murder Mysteries), Alfred Pennyworth (not to be confused with Pennywise the Clown), and Jeeves (of Jeeves and Wooster fame). We previously talked about Willikins and the “battle butler” trope in #Pratchat27, “Leshp Miserablés”, when discussing Jingo.

- The line about a god of policemen does not actually appear in Feet of Clay (#Pratchat24), and Vimes doesn’t say it – though it is attributed to him. In The Last Hero (#Pratchat55), when Carrot arrives in Dunmanifestin, chief god of the Disc Blind Io asks Carrot if there’s a god of policemen. ‘No, sir,’ Carrot replies. ‘Coppers would be far too suspicious of anyone calling themselves a god of policemen to believe in one.’ There’s also this line from near the start of Night Watch (#Pratchat54), which explains why most Watch members are buried in the Cemetery of Small Gods: “Policemen, after a few years, found it hard enough to believe in people, let alone anyone they couldn’t see.”

- Despite his self-doubt, Ben is right: igneous rock is indeed formed by volcanoes. Specifically, igneous rock is formed from cooled magma or lava, forms of molten rock that naturally occur beneath the Earth’s crust but come nearer the surface in volcanos (magma) or are released during an eruption (lava).

- Liz and Ben are both sort of right about the difference between concrete and cement. Cement is the binding agent used to make concrete, mortar, stucco and grout. It’s a combination of limestone, clay, shells and silica sand, which is mixed with water and then sets hard when it dries out. It’s not often used on its own, but instead combined with aggregate (a mixture of gravel and sand) to make concrete, which is the hard substance used for footpaths, driveways and structures. Most cement today is “Portland cement”, a fine grey powder developed in the 19th century by father and son Joseph and William Aspdin, who named it for its resemblance to Portland stone from the island of Portland in Dorset in the south of England. It mostly replaced the use of hydraulic lime, or “quicklime”. Cement is also combined with sand to make mortar, the “glue” that holds bricks together, and stucco, also known as render, used as a wall covering and to fashion ornamentations; and grout, used to fill the gaps between tiles. While all three use the same basic ingredients, they use different recipes, techniques and additives to achieve different consistencies suited to each use.

Thanks for reading our notes! If we missed anything, or you have questions, please let us know.