#Pratchat29 Notes and Errata

These are the show notes and errata for episode 29, “Great Rimward Land“, featuring guest Fury, discussing the 1998 Discworld novel The Last Continent.

Iconographic Evidence

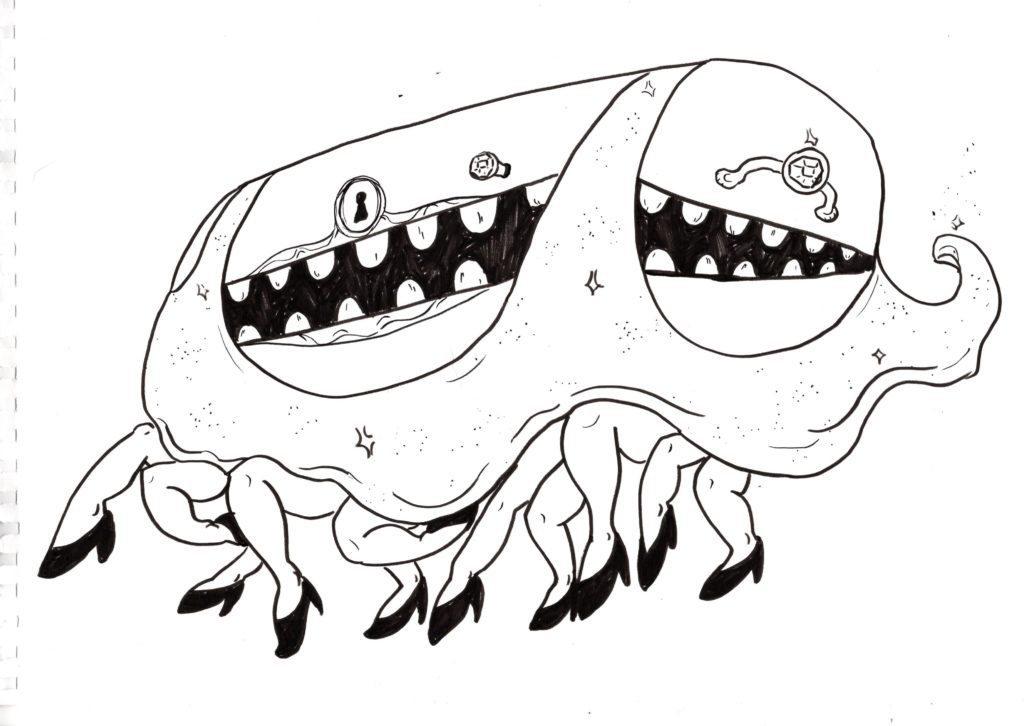

Feast your eyes on Fury’s glorious illustration of Trunkie!

Notes and Errata

- This episode’s title puns on the Icehouse song “Great Southern Land“, a big hit in Australia which also featured on the soundtrack of Yahoo Serious’ 1988 Australian comedy film Young Einstein. In retrospect both the song and the film might have been expected to show up parodied in The Last Continent – especially the song, since Pratchett listed it as one of his tracks when he appeared on Desert Island Discs in 1997. (Thanks to Al of Desert Island Discworld for this fact!)

- Our pre-show disclaimer uses the phrase “going off like a frog in a sock”. “Going off” on its own means to put a lot of energy or excitement into something, sometimes in anger, but in the frog idiom always in a fun way. Unusually for Australian slang, this isn’t ironic, just a straight-up metaphor; imagine you’ve caught a frog in a sock and it’s trying to get out, and you’ll get the idea. (And no, Australians don’t actually catch frogs in socks, this is strictly a thought experiment.)

- The Kiwi-Aussie portmanteau is spelled “Kaussie“, whereas the slang for swimwear is “cossie“; it’s short for “swimming costume”.

- The South Australian television personality who keeps getting in fights on the Internet is Cosi, host of South Aussie with Cosi, a travel show produced by Channel 9. (Not to be confused with Cosi, the play by Australian playwright Louis Nowra, previously discussed in #Pratchat23, “The Music of the Nitt“.)

- “Swimming togs” comes from the British slang word “togs”, which just meant clothes. It’s one of a number of slang terms now archaic in the UK which have survived in some form in Australia.

- Helen Zaltzmann is host of The Allusionist, a podcast about language, and one of Ben’s favourites. We’re sure she’d be the first to tell you that not every word – slang or otherwise – has a satisfying true origin story.

- Stephen Briggs was a frequent collaborator with Terry, beginning with the original map of Ankh-Morpork. He also contributed to the diaries, The Discworld Companion and many other books outside the main novels. He adapted many of the books into plays, some of which have been published, and has read the audiobook versions of more than 30 of Terry’s novels. (Stephen Fry reads the UK editions of the Harry Potter audiobooks; if you’ve heard the US versions, those are read by Jim Dale.)

- Mike Schur’s afterlife sitcom The Good Place set much of its third season in Australia, and copped much criticism from actual Australians for the quality of the accents. You couldn’t fault the jokes, though – or the punny names of the restaurants, shops and incidental characters in those episodes.

- Pretty Little Liars is a teen mystery TV series based on the books by American YA author Sara Shepard. The UK accented character is antagonist Alex Drake, who shows up in season 7. We’d tell you more, but…spoilers.

- The extreme Australian wizard slang originated in a reply to a tumblr post from about JK Rowling’s the introduction of the American term for muggle, “no-maj”; you can find the original here, but just in case it vanishes from Tumblr forever, we’ll immortalise the words of user edenwolfie here (and a quick warning – we haven’t censored the print version). We’d also like to point out that Australian wizards and witches would most likely spell it “muggo”.

I can just imagine the Australian word being some awful slang that’s derived from muggle, such as “mugo”.

Ah, I can imagine it now, wizards in thongs, drinking butter-VB yelling “You’re such a fucking mugo, you wandless cunt!”

edenwolfie, Tumblr, 11 November 2015

- Minotaur is Melbourne’s biggest independent pop culture and science fiction bookstore. Many of Terry’s early Melbourne signings occurred at its original location on Bourke Street, but it moved to Elizabeth Street in 2000.

- PhanCon ’98 was a one-off fan science fiction convention held in Sydney in 1998. Information on it is in short supply, but guests included Terry Pratchett and British fantasy author David Gemmell.

- Comet Shoemaker-Levy-9 broke up in 1992 and smashed into the planet Jupiter in 1994, to much excitement (on Earth at least). It was named for astronomers Carolyn Shoemaker, Eugene M. Shoemaker and David Levy, who discovered it after it had been captured by Jupiter’s gravity into a decaying orbit.

- English scientists did indeed doubt the reality of the platypus, which not only has a unique and wonderful anatomy, but is one of just two surviving monotremes – a group of mammals that lay eggs. (The other one is the echidna.) As well as its distinctive bill, it has sharp ankle spurs which in the male can inject venom, and the ability to sense electric fields as a way of locating prey.

- The Dreaming is a sophisticated concept in the stories of Aboriginal cultures. It has a complex relationship to space and time, existing both long ago and now, but despite the name – which was coined by Europeans – it has nothing to do with dreaming. An older term, “dreamtime”, is generally no longer considered appropriate. We recommend reading up on the topic; one good place to start is this article at Common Ground.

- Boomerangs bought in stores and thrown to return are, indeed, toys. Hunting and war boomerangs were generally much larger, sharpened, and often had one wing longer than the other.

- The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert is a 1994 Australian comedy film which was a surprise box office hit often considered hugely significant in the history of queer cinema. It follows two drag queens (Hugo Weaving and Guy Pearce) and a trans woman (Terence Stamp) as they travel from Sydney through the outback to perform in Alice Springs. Though initially praised for its queer-positive message, the portrayal of Filipino character Cynthia attracted widespread criticism for relying on racist stereotypes of Asian women common in Australia. Original writer and director Stephan Elliott adapted the film into a stage musical, Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, in 2006; the musical retains the characters and plot more or less unchanged, but hasn’t been criticised nearly as much for the character of Cynthia.

- The opal fossils gallery at the South Australian Museum is still there, and you can see the skeleton Ben mentioned. The web site is sketchy on details, so we can’t confirm if it’s an Elasmosaurus or another species of plesiosaur, but we still recommend you check it out yourself!

- The protagonist wizard (or at least wizarding student) in Moving Pictures was Victor Tugelbend. Other wizards not part of the regular faculty include Drum Billet, Archchancellor Cutangle, Simon and Esk (Equal Rites); Igneous Cutwell (Mort); Alberto Malich (Mort and most other Death novels); and Ipslore the Red (Sourcery).

- Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency is more-or-less a mashup of two of Douglas Adams’ Doctor Who scripts: the unfinished Shada, and City of Death, which contributed the storyline about time-travelling aliens who crash on Earth in the distant past and spark life on the planet. There are other elements in it which are wholly original, perhaps most notably the Electric Monk. This description applies to the original novel; the television adaptations, especially the US one, are very different.

- Mot was indeed a French cartoon series about a purple monster who could travel through time and space, taking his young friend Leo on various adventures. It was based on the French children’s comics created by Alfonso Azpiri. It was aired on Australian television in the late 1990s.

- Thanks to listener and supporter Molokov, who pointed out that Rincewind’s magical ability to find “bush tucker” might be a reference to retired army Major Les Hiddins, aka “the Bush Tucker Man“. Hiddins researched Australian native foods as part of his army career by working with Aboriginal peoples, mostly in northern Australia. He came to national fame through The Bush Tucker Man television series on the ABC in the late 80s and early 90s. In each episode Hiddins, wearing his trademark larger-than-usual Akubra hat, visited a part of Outback Australia and introduced viewers to the local edible plants and animals. Hiddins wrote several books, and then disappeared onto a remote retreat he created in the bush for retired army service people, before returning to the public eye in 2019 with a new website: bushtuckerman.com.au

- We discussed Interesting Times back in episode 21, “Memoirs of Agatea“.

- Black Sheep was released in 2006, written and directed by Jonathan King with special effects by Peter Jackson’s Weta Workshop. It seems the main way to watch it now is via the Amazon Prime Video streaming service, though it should also be available on DVD.

- Terry has not always had kind things to say about Rincewind; he suggested the wizard’s job is “to meet more interesting people” than himself, lamented Rincewind’s lack of an inner monologue, and did indeed feel like he was running out of things to do with an eternally cowardly character. Agatha Christie’s negative feelings about Poirot are well-documented, from as early as 1930; in a notable quote from 1960 she describes him as a “detestable, bombastic, tiresome, ego-centric little creep”. But she refused to kill him off because she felt she had a duty to keep writing about a character that was still so popular with the public.

- Michael Moorcock was an English fantasy author who created a number of characters including Elric of Melnibone, one of several incarnations of “the Eternal Champion”, fated to be reborn through the ages and battle in the primeval war between the forces of Law and Chaos.

- We discussed Only You Can Save Mankind in our previous episode, “All Our Base Are Belong to You“.

- Skippy the Bush Kangaroo (aka Skippy) was an Australian family television series about an usually smart kangaroo who helped park ranger’s son Sonny have various adventures. It was very much in the mould of Lassie or Flipper. It ran from 1968 to 1970, and there was a brief sequel series in 1992 featuring Sonny as an adult. It was broadcast in most Commonwealth countries, as well as the US and many Spanish-speaking countries including Mexico, Cuba and Spain.

- We’ve mentioned it before, but you can find the Annotated Pratchett File at the old L-Space Web site. Its successor is the L-Space Wiki.

- The Moa is a large extinct flightless bird, similar to a Cassowary. Like many megafauna of Australia and New Zealand, they were hunted to extinction, in the Moa’s case by the Māori peoples.

- “Jeremy Bearimy” is an explanation of how time works in the afterlife in the sitcom The Good Place. Rather than a straight line, the flow of time there resembles a curve which looks like a signature reading “Jeremy Bearimy”. The dot in the i (or tittle) is a weird separate bit of spacetime.

- “Guzzaline” was the term used for petrol in Mad Max: Fury Road, the fourth Mad Max movie, released in 2015. It stars Charlize Theron as Imperator Furiosa, a driver for a despotic warlord in post-apocalyptic Australia. Tom Hardy appears as Max Rockatansky, the titular character, who was the protagonist of the previous three films, where he was played by Mel Gibson.

- When Liz refers to Darwin, she means the city, which is the capital of Australia’s Northern Territory. It was named for Charles Darwin by John Clements Wickham during a subsequent voyage of the ship Darwin took on his famous voyage, the HMS Beagle.

- In Jurassic Park, palaeontologist Alan Grant claims to know that the Tyrannosaurus rex – portrayed in the films as a ferocious predator – has vision “based on movement”. This is one of many things that make no sense in the film. Have a few drinks with Ben, or your local friendly palaeontologist, and they’ll tell you about some others.

- Richard Dawkins is now best known for heavy-handed criticism of religion and, most recently, feeling the need to confirm that whatever you think of it, eugenics works. But he initially found fame for his pretty good books on evolutionary biology. In The Selfish Gene, first published in 1976, he popularised the idea that the gene is the basic and most important unit of evolutionary information, and also coined the term “meme”, meaning the behavioural or cultural equivalent of a gene.

- Historians, archaeologists and anthropologists frequently find evidence that revise the likely length of Aboriginal culture’s existence in Australia about every six months – usually making it older. Current estimates range from 50,000 to 125,000 years.

- You can read about the Sydney baboon escape from late February 2020 in this article at The Guardian – written by previous Pratchat guest, Stephanie Convery! (Steph was a guest in #Pratchat2, and later returned for #Pratchat42.)

- You certainly used to be able to get tea-towels and such that were supposedly from “Didjabringabeeralong, The Outback”, but these days we’d like to think we’re a bit more culturally sensitive. The unique names of many Australian towns and cities – like Wagga Wagga, Geelong and Nar Nar Goon – are drawn from local Aboriginal languages, many of which have been lost as those peoples were displaced or massacred by Europeans.

- Tank Girl is a punk-inspired comic book series by created by British writer Jamie Hewlett and artist Alan Martin. Tank Girl is the main character, who lives in a tank in post-apocalyptic Australia. She’s accompanied on her adventures by her mutant kangaroo boyfriend, Booga. The comic was adapted into the 1995 film Tank Girl, directed by Rachel Talalay and starring Lori Petty as Tank Girl and Naomi Watts as her friend Jet Girl (who has a jetpack), with Malcolm McDowell as the antagonist. It has a cult following but was not a big success.

- Listener Ian Banks in our Discord pointed out that another, probably more likely inspiration for the anthropomorphic animals is The Magic Pudding, a 1918 children’s book written and illustrated by famous Australian artist Norman Lindsay. The story’s main characters are Bunyip Bluegum (a koala person), human sailor Bill Barnacle, and Sam Sawnoff (a penguin person). The titular pudding, Albert, has a face, arms and legs, and regenerates, so he can supply an infinite amount of food. The story also features “pudding thieves” Patrick and Watkin, a possum and wombat respectively.

- We want to make it clear that despite Liz’s hangups, marsupial pouches are not dirty; kangaroos lick theirs clean before their joeys enter them.

- Barry McKenzie, a creation of Australian comedian Barry Humphries, began life as a comic strip character in the pages of UK comic magazine Private Eye in 1964. A parody of the Australian abroad, he is a hard-drinking, womanising, simple-but-forthright “larrikin” who gets himself into various scrapes. He was played by singer and actor Barry Crocker in two films in the 1970s, which also introduced Humphrie’s long-running character Dame Edna Everidge, who is Barry’s aunt. The films nearly killed director Bruce Beresford’s career, but he later went on to find fame and success, with such big films as Driving Miss Daisy and Mao’s Last Dancer.

- “Squids” in the book is almost certainly a pun on “quid”, slang for a pound sterling in the UK and pre-decimal Australia. It’s still used occasionally as slang for money in Australia, usually in the phrase “a few quid”.

- In case you missed it, the shearing competition in the book is clearly inspired by the Australian folk song “Click Go the Shears“.

- We cut the discussion for time but “something for the weekend” reminded Ben of ska band Madness’s song “House of Fun”, which is about a teenager who has turned sixteen and is using various euphemisms to try and buy condoms at his local chemist.

- In The Man From Snowy River, the actual description of the hero’s horse is “something like a racehorse undersized”.

- As alluded to in the book, drop bears are a fictional cousin of the koala, a horrible killer animal which waits in treetops to drop on and eat children. Inventing dangerous creatures has been a long-running prank played on visitors to Australia, playing on their fears of the real deadly animals that live here. A recent incidence of the drop bear was this prank played on a UK reporter visiting to report on the bush fires.

- The bush ballad “Waltzing Matilda” is thought by academics to describe the Great Shearer’s Strike of 1891, in which shearer’s killed a number of sheep and one of their number, being chased by police, killed himself rather than be taken alive. A lot of the slang in the song is never heard anywhere else anymore – including “jumbuck”, a term for sheep thought to have been derived from an Aboriginal language. There are many versions of the lyrics, but the most famous one was adapted by the Billy tea company. In some, Liz’s question becomes moot, as the troopers ask “Whose that jolly jumbuck”, rather than “Where’s“.

- If you’re confused by Liz’s “cat in a bag” antics, you can read about Schrodinger’s Cat and other feline behaviours in our discussion of Pratchett’s non-fiction humour book The Unadulterated Cat. You’ll find it in #Pratchat22, “The Cat in the Prat“.

- The Domestic Blindness sketch was indeed part of vintage 1980s Australian sketch comedy show The Comedy Company; you can find it on YouTube here.

- Listener and previous guest Avril (who you might remember from #Pratchat16, “He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Vorbis“) points out that the god’s love of beetles is likely a reference to English geneticist and evolutionary biologist J. B. S. Haldane, perhaps most famous for writing about abiogenesis and the idea of “primordial soup”, among many other accomplishments. In response to being asked what his study of nature might reveal about the Creator, Haldane is perported to have said “that He is inordinately fond of beetles”, due to the phenomenal number and variety of beetle species. While this exact response might be apocryphal, he definitely said something equivalent many times, both in print and in speeches.

- Gachnar the Fear Demon appears in the fourth season Halloween episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, “Fear, Itself”, from 1999.

- Australian cockroaches are not actually Australian at all – they live all over the world, and probably originally come from somewhere in Africa.

- White-tailed spiders are small spiders native to south-eastern Australia. They are not aggressive but might bite if disturbed, and like to hide among leaf litter. They were demonised in the media during the late twentieth century as their bite supposedly caused necrosis, but medical research in the early twenty-first century didn’t find evidence of any such symptoms. Instead, the spider’s venom caused only unpleasant but mild symptoms, especially by Australian standards.

- The Stonefish is a real fish, one of the most venomous in the world. It disguises itself as a stone in order to catch smaller fish as prey, but has sharp spines on its back which deliver venom as a defence against predators. Four of the five species live outside Australian waters; their sting can be treated with hot water (which denatures the venom) and anti-venom.

- Last Chance to See was a 1989 radio documentary following Douglas Adams and zoologist Mark Cawardine as they travelled the world to visit nine different endangered species. Adams turned it into a book in 1990, and in 2009 Stephen Fry joined Cawardine for a sequel television series, accompanied by a new book.

- Pauline Hanson is a right-wing populist politician from Queensland who rose to fame when she ran for federal parliament in 1995 as a member of the conservative Liberal Party. They dis-endorsed her after she made racist comments about Aboriginal Australians, and she formed her own party, One Nation, and won a seat. She was found to have committed electoral fraud and jailed, though the charges were subsequently overturned on appeal. She left her own party in 2002 over those charges, but remained a figure in the Australian media, aided by appearances on breakfast television and the reality show Dancing with the Stars. She returned to politics and One Nation in 2013, and was elected to the Australian Senate in 2016. She is famous mostly for various racist views that very much align with those of Fair Go Dibbler.

- Lost is a TV series about a bunch of plane crash survivors who find themselves lost on a mysterious island. It famously makes no sense whatsoever and it’s generally considered that it’s creators, JJ Abrams and Damon Lindelof, were making it up as they went along to stay ahead of the guesses of fans on the Internet about what was really going on.

- The Galah (pronounced “ga-LAR”) is a large, loud pink and grey cockatoo (a type of parrot), common in many parts of Australia. “Galah” is also slang for a ridiculous or foolish person.

- The Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras is a one of the largest pride parades in the world. It happens annually on the first Saturday in March, and started in 1978. It draws massive crowds from all over the world.

- Intersex people are born with genetic and/or physical characteristics associated with both of the traditional genders. While the statistics are sometimes contested, it’s thought as many as 1.7% of people are born with some kind of intersex characteristics. The I in LGBTIAQ+ is for intersex.

- The infamous Australian episode of The Simpsons, “Bart vs Australia”, is from the show’s sixth season in 1995.

- The tough guy who appreciates art in Thief of Time is probably Newgate Ludd.

- Damian Callinan’s The Merger started life as a one-man show, but was adapted in 2018 into a feature film. You can find it on the free streaming service Kanopy if you are a member of a library that subscribes to it, and its now on Netflix in many regions too.

- The original Harry’s Cafe de Wheels started out in Woolloomooloo, a harbour-side inner suburb of Sydney, as a “caravan cafe” specialising in serving late night pies. It was founded by Harry “Tiger” Edwards in 1936. It’s been patronised by many international celebrities and there are now several Harry’s cafes around Sydney and New South Wales – though not, despite Ben’s later confusion, in Adelaide.

- The word for the smell you get after it rains – specifically, the smell of earth after it rains – is “petrichor”. Hopefully it’s okay for us to use it as we’re not writing a poem.

- Tropical areas – such as the northern part of Australia – are often described as having Wet seasons and Dry seasons. The Wet season is also known as monsoon season or the Rainy season in some parts of the world.

- You can read about the six seasons described by the Kulin people of Melbourne on this web site.

- To avoid any confusion: in Good Omens, it’s said that any cassette tape left in the glove box of a car transforms into Queen’s Greatest Hits. In Mort, it’s said that no matter what’s put into it during the day, a pantry raided in the middle of the night contains only some very specific and disappointing items.

- “How to Make Gravy” is a 1996 song by Australian singer-songwriter (and national treasure) Paul Kelly. It was originally written and released as part of a Christmas charity album benefitting the Salvation Army, when Kelly found out the song he initially wanted to cover had already been picked by another band. In Kelly’s song the narrator, Joe, has been sent to prison; the lyrics are a letter he’s writing on December 21 (dubbed “Gravy Day” by some fans) lamenting that he won’t be home for Christmas, and giving his brother his gravy recipe, since that’s his usual contribution to the Christmas cooking. It became a surprise hit and was nominated for the APRA song of the year award in 1998. Below is the official video. (We’ll mention the song again in the Oggswatch Feast 2021 bonus Christmas episode.)

- Captain Raymond Holt is the captain of police precinct 99 in the sitcom Brooklyn-99. He – like all the characters in the show – is wonderful.

- Umami is the “fifth taste”, after the other basic tastes of sweet, sour, bitter and salty. The word comes from Japanese, and translates as “pleasant savoury taste”, being derived from the word umai, “delicious”. Other foods with an umami taste include various vegetables, mushrooms, shellfish, cured meats and green tea.

- Barnaby Joyce is (as of March 2020) the current leader of the National Party, a conservative party popular in rural areas. They have a long-standing coalition with the Liberal Party; the Liberal-National coalition are currently in government. Tony Abbott is a former leader of the Liberal Party who was Prime Minister of Australia for a brief period, before being ousted in favour of the more moderate Malcolm Turnbull. He lost his seat at the last federal election. Both are pretty weird units, to use an Australian phrase, with their share of scandals, bizarre behaviour and controversy.

- “Where the bloody hell are you?” was the key question asked by model Lara Bingle at the end of a largely ridiculed Australian tourism ad produced for the international market in 2006. It was controversially banned on release in the UK, despite costing 180 million Australian dollars, and despite its infamy was considered a failure. It was overseen by now Prime Minister Scott Morrison, who at the time was Managing Director of Tourism Australia; this led to some reprise of the question directed at him – including by Bingle herself on social media – when he was overseas on vacation during the beginning of the disastrous 2019-2020 bush fires. It was also part of the inspiration for his derisive nickname “Scotty from Marketing”. You can watch the original ad on YouTube here.

- Paul Parker found internet fame after he angrily reacted to Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s comments that members of Australia’s volunteer fire fighting organisations “want to be out there” fighting the unprecedentedly fierce bushfires that raged in late 2019 and early 2020. In a video that went viral, he leaned out of his firetruck and asked a Channel 7 news crew to tell the Prime Minister to “go and get fucked from Nelligen”. After there were (disputed) claims this got him sacked from the Rural Fire Service (a volunteer organisation), another video emerged of him saying that Pauline Hanson was the only politician who cared about Australia. The whole saga is covered by Jan Fran in her first “The Frant” video for The Guardian.

- “I’m not here to fuck spiders” is a slang expression meaning “I’ve got serious work to do,” most often used in response to a question about one’s intentions. It is also used as a more emphatic version of “I’m not here for a haircut”, which is a sarcastic response to being asked if one has come to a place to do the obvious thing, like being asked in a car dealership if you want to buy a car. It’s been a matter of debate for some years whether “not here to fuck spiders” is a “real” expression, or if it was invented as a joke and since been embraced by Australians. Looking through Google’s trends tool, which goes back as far as 2004, the first and biggest spike in searches for the phrase is in November 2005; then there’s very little until it slowly increases in search popularity from 2010, with smaller spikes since 2018 where it has been mentioned by Australian celebrities. The only reference Ben could find from 2005 were a series of replies to a forum post asking about the phrase, many of which seemed to suggest straight up examples of having heard it years before that… It’s worth mentioning that one of the repliers had come to the thread because they heard it from an Australian comedian, which might mean it was made up as a joke, or it could just mean that was the first time people who didn’t get it were hearing it.

- The Man From Snowy River television show is not actually related to the 1982 film starring Sigrid Thornton and Tom Burlinson. The TV series starred Andrew Clarke as Matt McGregor, the stockman from the poem, and is set 25 years after the events depicted in the poem. It ran from 1993 to 1996.

- Bore water is water drawn from underground sources, usually by drilling a borehole into an artesian aquifer – a porous underground layer of the Earth’s crust in which water is stored or flows. In Australia, the source is most commonly the Great Artesian Basin, a huge artesian aquifer under large parts of Queensland and its neighbour states.

- “Advance Australia Fair” has been the official Australian anthem since 1984, though it was written far earlier, in the late 1870s. It was chosen in a plebiscite attached to the 1977 referendum about voting and political reforms. It beat “Waltzing Matilda”, “The Song of Australia”, and the previous anthem “God Save the Queen”. (For more on this, see #Pratchat53, “A (Very) Few Words by Hner Ner Hner“, in which we compare the Australian and Ankh-Morpork national anthems.)